In a dramatic move just before stepping down, Israel’s Minister for Jerusalem Affairs and Jewish Tradition, Meir Porush, instructed officials to implement an expropriation decree issued shortly after the 1967 war. The order targets Palestinian-held assets along Chain Street (Bab al-Silsila), adjacent to some of the most sensitive religious and political sites in Jerusalem’s Old City

The original decree, issued in the wake of the Six-Day War, was partially implemented to expand the Jewish Quarter. However, key properties on the eastern face of Chain Street were left untouched due to their extreme religious and diplomatic sensitivity — especially given their proximity to the Western Wall, the Temple Mount, and Al-Aqsa Mosque

Porush’s directive was sent to the state-run Jewish Quarter Development Company, which manages the area. In his letter, he wrote

“This street holds strategic and historical significance. It is time to assert sovereignty and realize ownership. I believe this will ultimately bring greater security to residents and visitors alike

He ended the letter with a quote from the Book of Zechariah: “And I will rebuild Jerusalem and show her mercy

(Donkey’s Head on Cemetery Fence: Jerusalem Man Jailed)

A Landmark of Islamic Heritage

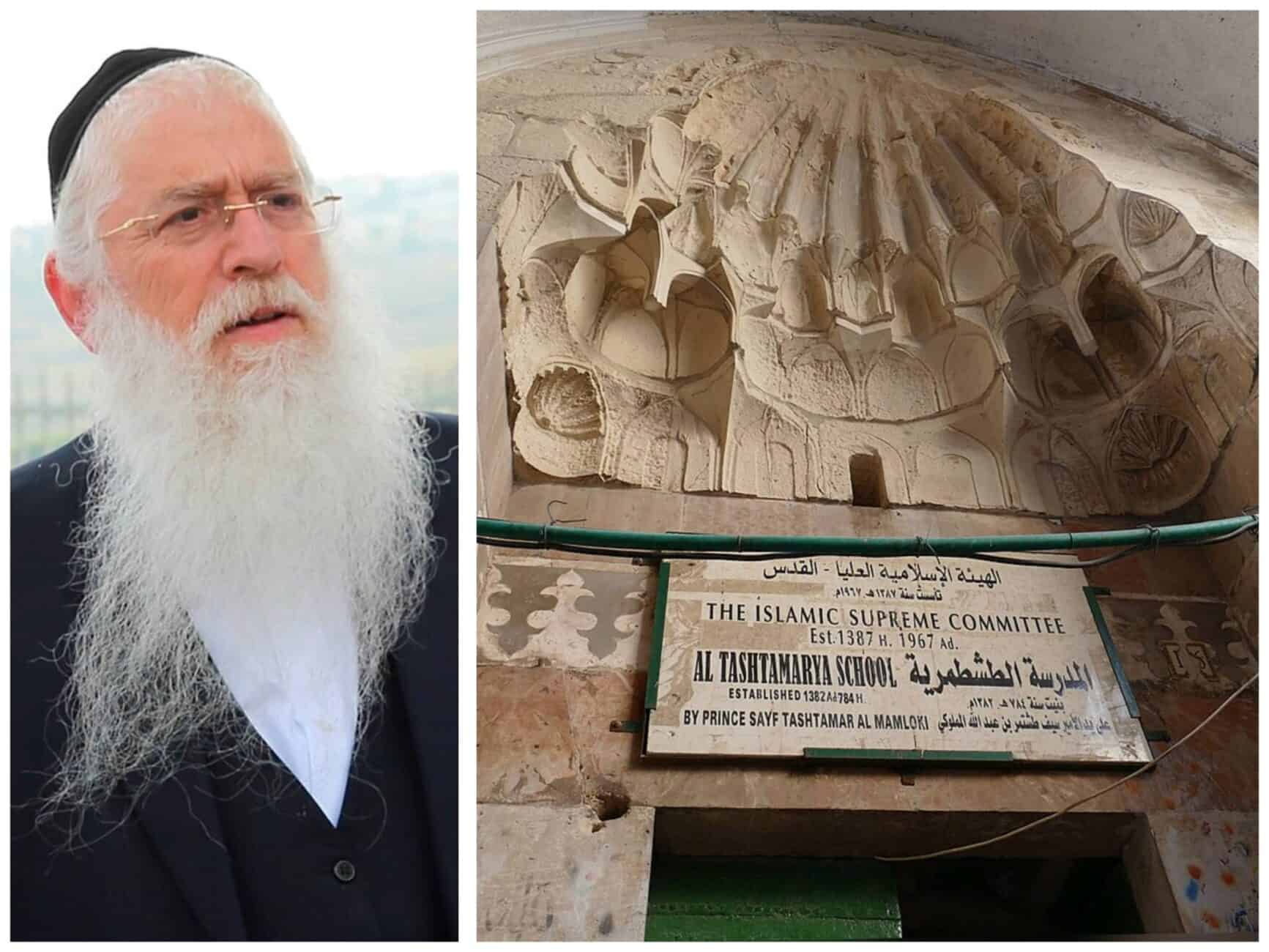

One of the most prominent structures mentioned in the decree is the Al-Tashtamariya Madrasa, built in 1382 by the Mamluk emir Tashtamur al-Ala’i. Originally a prestigious Islamic school, the structure now houses Palestinian families in its upper floors, commercial shops on street level, and the headquarters of the Islamic Supreme Council, led by Sheikh Ekrima Sabri a former Mufti of Jerusalem known for his vocal opposition to Israeli control over the Temple Mount

The madrasa is one of three major Islamic institutions built in the Mamluk era around Al-Aqsa, and remains a focal point of Palestinian historical identity in Jerusalem

Markets, Morabiton, and Tensions

The decree also encompasses additional Palestinian-owned assets with deep historical roots, including Khan al-Fahm (a former coal trading hub), the vibrant Suq al-Shawaya (known for meat grilling), and Suq al-Mubayidin, where textile artisans once bleached cloth

(Jerusalem in Mourning: Three Weeks of National Introspection)

Palestinian voices connect Porush’s move to broader efforts to suppress the Murabiton — a group of Islamic activists who once patrolled the Temple Mount and now gather outside the Chain Gate. Their removal from the Mount by Israeli authorities was widely perceived as a blow to Palestinian presence there. Many fear that this latest expropriation move aims to push them further away

Across Jerusalem and the Arab world, reactions to the minister’s directive have already sparked concern — not only over property rights but over what it symbolizes: a possible shift in Israel’s long-standing approach to coexistence in the most contested corridor of the Old City